I am a first year math interventionist at the small central Maine school where I previously taught 4th grade for 7 years. As a classroom teacher, I grew passionate about creating inclusive communities of mathematicians. As an interventionist, I’m trying to find ways to continue this work throughout our K-5 school. I’ve started with my friend and co-teacher Carolyn, who teaches 3rd grade and shares the belief that all of her students have valuable contributions to make in her classroom.

“Angie” is a 3rd grade student in my school. She is an amazing mathematician. I work with Angie in her classroom every day while I co-teach with Carolyn, and I also see her outside her math block for 15 minutes each day. Angie’s attendance has impacted her access to the curriculum over the past few years. When I first started working with Angie at the beginning of the year, she was working toward first grade standards. She was unsure about her competence, and was hesitant to share her ideas. She has made so much progress since then, and not just with the math content we have worked on through the year. She shares her thinking in class, will try a problem without the help of a friend or teacher, and will even disagree with a classmate when they have different answers. She knows she is a valuable member of her classroom, and her confidence as a mathematician is through the roof.

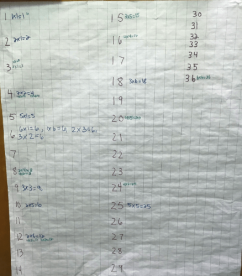

Angie has been working on multiplication with me in our time together. We’ve been using Marilyn Burns’ Do the Math intervention program in addition to some work from our district curriculum that she missed due to absences. I look forward to my time with Angie every morning. Within these lessons, we started a list of multiplication facts that she has been working on with a list of products from 1-36. Next to every product, we write the equations that make that product. Angie owns this list. She decided early on that she did not want to add to this list until she was sure that the fact was correct. She really values being precise and accurate. We even use Sharpies! She has been working with facts from 1×1 to 6×6.

A few weeks ago, she noticed something. She said to me, “I’m wondering about the numbers that have no facts next to them. Why is that? Like 11 and 13 and 22 and 23.” I said “That’s a really interesting observation. What do you think?” Angie thought for a minute, and then said, “I’m not sure. Maybe it’s because we haven’t worked on 7s, 8s, and 9s?”

I asked her if she’d like to work on those fact the next week, and she left very excited. In fact, when I saw her after the weekend, she had been thinking about those facts already. She told me she knew 1×7 and 2×7, 1×8 and 2×8, 1×9 and 2×9. She also told me that if you made the array and rotated it (she indicated how she would rotate the arrays with her hands), she would know 7×1, 7×2, 8×1, 8×2, 9×1, and 9×2! She was so excited to add these facts to her chart. When she finished, she sat back and said, “But there are still numbers without any facts. Why?”

Of course, like most amazing questions, this question came right at the end of our time together! I promised Angie that we would explore that the next day. When she came in the next day, she said, “We have more work to do.” She wanted to build arrays with new facts. We worked on 7, 8, and 9 facts with factor pairs up to 6. It was really hard work, but her question motivated her. Whenever she found a product, she hurried across my tiny room to add it to the chart.

She also had some great wonderings about how to find all the factors for a number. As she was working on 11, I recorded our conversation:

”I think nothing will fit on them except ones.”

“Can you prove that?”

Angie reached for the tiles, and tried to make arrays with factors of 3, 4, 5, and 6. She shook her head and tried a new number each time until she stopped at 7. She made one row of 7, and shook her head again.

“But 7 is too high a number! You would never be able to use that to make a rectangle. You’d need 3 more,” she said, indicating the 3 empty spots in her 2 x 7 array.

I pushed her harder. “What about 8?” “Nope,” she said confidently. “Why not?” I wondered. “Well…it’s like if you can’t make 2 [pointing to the rows] that are all filled, it will never work. So, like, with 7 you can’t make 2 rows. You can’t with 6 either! You could with 5…but there would be this extra one, so that’s not an array.”

I was floored – again! This idea is something that usually took my FOURTH graders a long time to realize when we studied prime and composite numbers, and here was my intervention student coming to that conclusion in third grade.

She eventually made another connection. “Mrs. Hatt,” she said to me when she came in one morning, “I have a fact for every number now. One can be a factor in any of these numbers. So you can have 1 x 11 and 11 x 1, and that will work for every number we have on the chart!” I asked her how she knew, and she got out tiles to make an array and explained that you can have __ groups of 1, or 1 group of ___. She added excitedly, “You could even have 1 times a million, or a million times 1!”

I was continuously bragging about her to Carolyn, and during one of our conversations, Carolyn said, “Angie has to share what she’s learned with the class!” I literally gasped. It was an awesome idea. In the classroom, we had arrived at the area and perimeter unit, and were deep in the work of arrays again. I was so excited for the possibility of Angie sharing her learning with the class. Not only was she really owning the idea of multiplication, she was considering the idea of prime and composite numbers, a 4th grade standard!

The next day, I excitedly shared our idea with Angie. We were doing so much multiplication work in 3rd grade – would she want to share all the work we had done together? Angie was horrified by the idea. She did not want to speak to her entire class. She said, “Can’t you just do it?” I talked to her about doing it together and about how useful it would be to her class. She was not convinced. All of a sudden, I saw the old, timid Angie come out. She said, “I think everyone will already know this stuff.”

I don’t want to make Angie share her chart, but I see so much value in it. She has ideas that, despite what she thinks, other 3rd graders haven’t considered yet. But she’s clearly not feeling ready for it. I attempted to talk to her a couple more times about it, and she shut me down each time. I struggle with how much to push a kid – will that push be just the thing she needs, or so much that her confidence is shot? In those moments, I sensed that I shouldn’t push it.

Over the last weeks of school, I have lunch dates with kids almost every day. I’m having lunch this week with Angie and one of her 3rd grade friends. I’m thinking of starting small, during our lunch, by asking Angie to share what we did on the chart. Casual, friendly, a small audience. Maybe she’ll do it. Maybe not. But I think there is so much value in making kids aware that their ideas are important and worthy of being shared. I hope to do a lot more of this kind of work next year!

*Update:

Thanks everyone for all the positive feedback. It’s overwhelming! Today was our last day, and Angie’s teacher had all of the kids write compliments to each other to bring home. Several kids wrote “Angie is really good at math.” Angie also wrote a compliment to herself: “I am smart.” I love that Angie now truly believes this about herself. This type of progress is the most important to me as one of her teachers.

Angie did not end up sharing her chart with her friend, but asked to bring it home over the summer and add to it. I’m so inspired with her continued commitment to get to the bottom of this big idea. I can’t wait to see what she does as a 4th grader!